Hainikoye hits Settle for and a younger girl greets him in Hausa, a gravelly language spoken throughout West Africa’s Sahel area. She has three new cows, and desires to know: Does he have recommendation on getting them by the lean season?

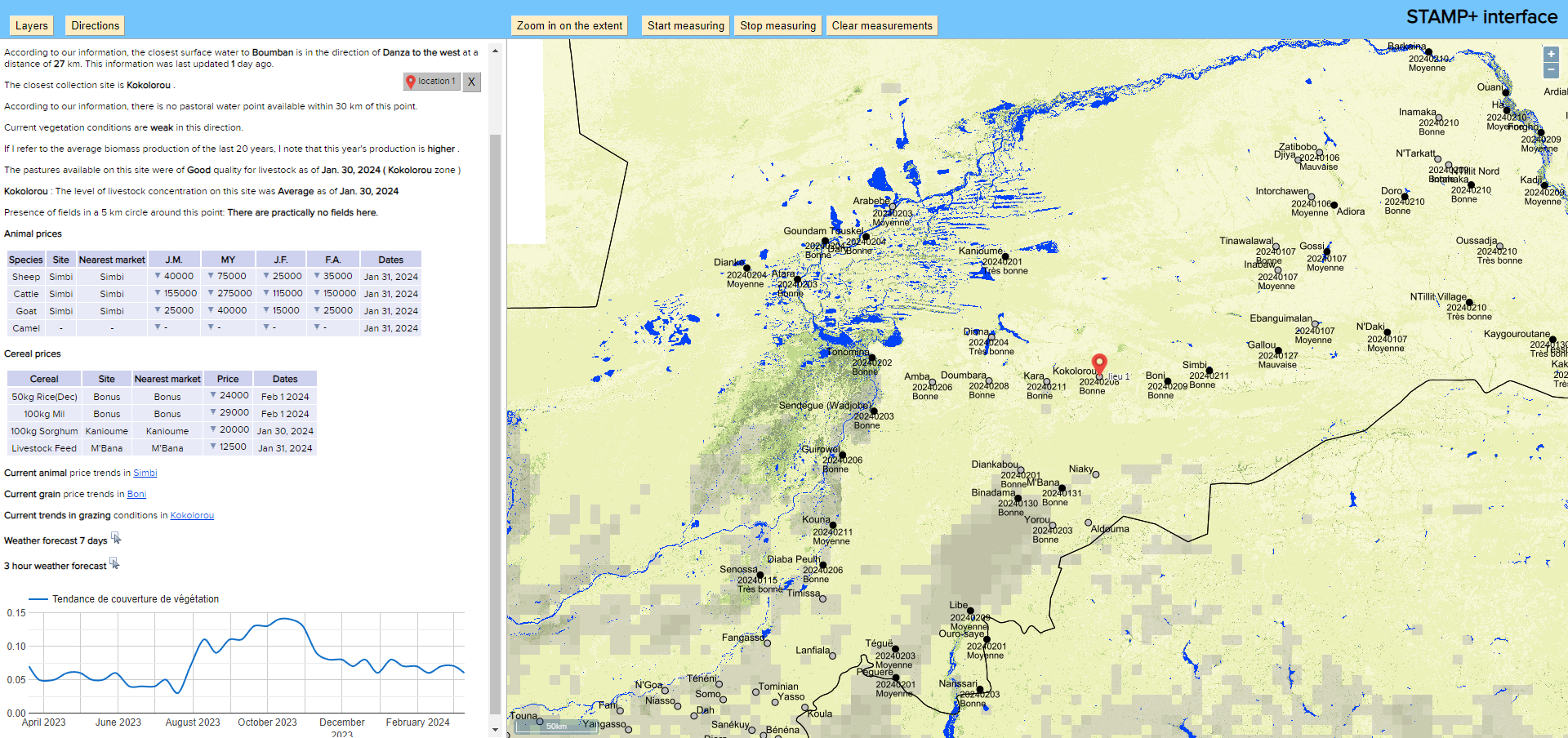

Hainikoye—a twentysomething agronomist who has “adopted animals,” as Sahelians seek advice from herding, since he first realized to stroll—opens an interface on his laptop computer and clicks on her village in southern Niger, the place humped zebu roam the dipping hills and dried-up valleys that demarcate the northern desert from the southern savanna. He tells her the place the closest full wells are and suggests feeding the animals peanuts and cowpea leaves—low cost meals sources with excessive dietary worth that, his display screen confirms, are at present plentiful. They cling up after a couple of minutes, and Hainikoye waits for the cellphone to ring once more.

Seven days every week on the Garbal name middle, brokers like Hainikoye supply what looks as if a easy service, treating folks to a bespoke collection of location-specific knowledge: satellite-fed climate forecasts and reviews of water ranges and vegetation circumstances alongside numerous herding routes, in addition to sensible updates on brushfires, overgrazed areas, close by market costs, and veterinary services. Nevertheless it’s additionally surprisingly progressive—and is offering crucial assist for Sahelian herders reeling from the consequences of interrelated challenges starting from warfare to local weather change. Over the long run, the mission’s supporters, in addition to the herders connecting with it, hope it might even safeguard an historic tradition that capabilities as an financial lifeline for all the area.

The shiny purple cubicles of Garbal’s workplace in Niamey, Niger’s capital, are tucked away within the second-floor house the decision middle shares with the native headquarters of Airtel, an Indian telecom. It had solely been open for just a few weeks after I visited early final yr. Bursts of fuchsia bougainvillea garlanded the entryway to the constructing, a welcome respite from the sand-colored panorama and sewage-infused scent of the rotting industrial district round it. One lot over sat a former Complete fuel station that has remained unbranded since a drug cartel purchased it to launder cash and eliminated the signal. Working throughout the zone was a boulevard commemorating a 1974 coup d’état, which has been adopted by 4 extra over the following 5 many years, the newest in July 2023. In the course of the boulevard sat just a few dozen miles of decomposing railway tracks that had been “inaugurated” by a right-wing French billionaire in 2016. For many years, postcolonial elites, promising growth, have pillaged certainly one of Africa’s poorest nations.

In more moderen years, numerous Western gamers touting tech traits like synthetic intelligence and predictive evaluation have swooped in with guarantees to resolve the area’s myriad issues. However Garbal—named after the phrase for a livestock market within the language of the Fulani, an ethnic group that makes up nearly all of the Sahel’s herders—goals to do issues in another way. Constructing on an strategy pioneered by a 37-year-old American knowledge scientist named Alex Orenstein, Garbal is targeted on how humbler applied sciences would possibly successfully assist the 80% of Nigeriens who stay off livestock and the land.

“There’s nonetheless this concept of ‘How can we use new tech?’ However the tech is already there—we simply must be extra intentional in making use of it,” Orenstein says, arguing that donor enthusiasm for shiny, advanced options is commonly misplaced. “All of our massive wins have come from taking some basic-ass shit and making it work.”

Garbal’s work comes right down to knowledge and, critically, who ought to have entry to it. Latest advances in knowledge assortment—each from geosatellites and from herders themselves—have generated an abundance of data on floor cowl amount and high quality, water availability, rain forecasts, livestock concentrations, and extra. The ensuing breakthroughs in forecasting can, in principle, assist folks anticipate—and defend herds from—droughts and different crises. However Orenstein believes it’s not sufficient to extract knowledge from herders, as has been the main target of quite a few efforts over the previous decade. It have to be distributed to them.

The work couldn’t be extra pressing. The area’s herders face an existential disaster that has already began to shred the very cloth of society.

Herding—prestigious, excessive threat, and certainly one of humanity’s most foundational methods of life—is a pillar of survival within the Sahel. In Niger, as an illustration, identified throughout the continent for its succulent steak, animal manufacturing accounts for 40% of the agricultural GDP. Migratory herders usher between 70% and 90% of the cattle inhabitants between seasonal pastures, since they not often personal land. These pastoralists have traditionally relied on frequent assets, in coordination with native communities.

However the conventional methods have gotten subsequent to not possible. The disaster stems, partially, from the altering local weather: because the desert creeps south, and because the dry season stretches longer and the rains are available in shorter and extra risky intervals, water, pasture, and different renewable assets are more and more erratic. However the pressure can be political: brutal preventing between pro-government forces and native teams with hyperlinks to Boko Haram, Al-Qaeda, and the Islamic State has turned main transit hubs, cow superhighways, and wetlands into battlegrounds. Making issues worse, herders are usually underrepresented inside state establishments, whose land-use insurance policies favor farmers, and overrepresented inside jihadist teams, which enchantment to this exclusion to attract recruits from herding communities. A standard lack of education amongst kids of herders additional deepens this exclusion.

The result’s that tens of tens of millions of Sahelian herders who rely on free motion are more and more penned in. Issues are particularly dire for Fulani herders, who get scapegoated as troublemaking outsiders. So addressing the multidimensional disaster wouldn’t solely assist herders; it might take away an intractable driver of certainly one of Africa’s worst wars.

“Making certain that herders have land and water rights, and understanding their entry to those by dialogue, is a vital a part of the answer to battle within the Sahel,” says Adam Higazi, a researcher on the College of Amsterdam and Nigeria’s Modibbo Adam College, whose 2018 report on pastoralism and battle for the UN’s West Africa workplace stays a key reference within the area.

The query now could be whether or not Garbal and a handful of different tech-driven tasks can in reality ship on guarantees to assist stabilize herders experiencing rising precarity.

Aliou Samba Ba, who leads a regional pastoralist group that has teamed up with Orenstein to get knowledge to Senegalese herders, says he’s optimistic, largely as a result of Orenstein is popping conventional interventions the wrong way up: “We are saying he appears to be like with the attention of the herder in addition to with the attention of the satellite tv for pc.”

When establishments fail

The Sahel stretches from Senegal’s Atlantic shoreline throughout Africa to the Pink Sea, bounded by the Sahara to the north and by verdant forests and savanna to the south. A lot of the area has been ravaged by drought and insurgencies over the previous few many years, however rural Senegal continues to be house to the varieties of areas that herders elsewhere are preventing for: maintained, not overdetermined; protected, not overpoliced. There’s local weather change right here, however no warfare.

Final September, I drove deep into the Ferlo, a pastoral reserve roughly the scale of New Jersey, to fulfill with a Fulani herder named Salif Sow.

It was the peak of the wet season, and the Sahel was having a fantastic one. The atmosphere that greeted me was a miracle and a mirage—a desert burst into bloom. Tall, bony Fulani herders scrambled to maintain up with throngs of lambs, goats, cows, and camels unfold out over a seemingly infinite expanse of inexperienced grass and lushly foliated bushes. The Ferlo was brimming with fastidiously maintained wells, abundantly stuffed seasonal ponds, and clearly marked pastoralist corridors, with the nation’s greatest wholesale livestock market just some hours’ journey by donkey cart. There have been no paved roads, no business farmland, and no extremist recruiters for a whole bunch of miles in any path.

Not that the herding was straightforward work. “A herder’s life is tough,” Sow mentioned, welcoming me to his compound with candy tea and a calabash stuffed with contemporary milk. “There’s not someday of relaxation.”

In just a few months’ time, the rains would cease, the herds would exhaust the pastures, and the grassland would revert again to abandon. And Sow would once more face the tough choice he faces yearly: whether or not to remain and purchase livestock feed to tide his animals over till subsequent yr’s rains or to steer his cows on a journey, and in that case, the place.

Lots of advanced spatial calculations go into selecting the place to take a whole bunch of hungry cows to attend out the dry season on the sting of the world’s largest subtropical desert, whereas ensuring they’ve sufficient to eat alongside the way in which. Observing these deliberations stuffed Orenstein with marvel greater than a decade in the past, when he began surveying herders in Chad for a meals safety mission with the French NGO Motion Towards Starvation (ACF).

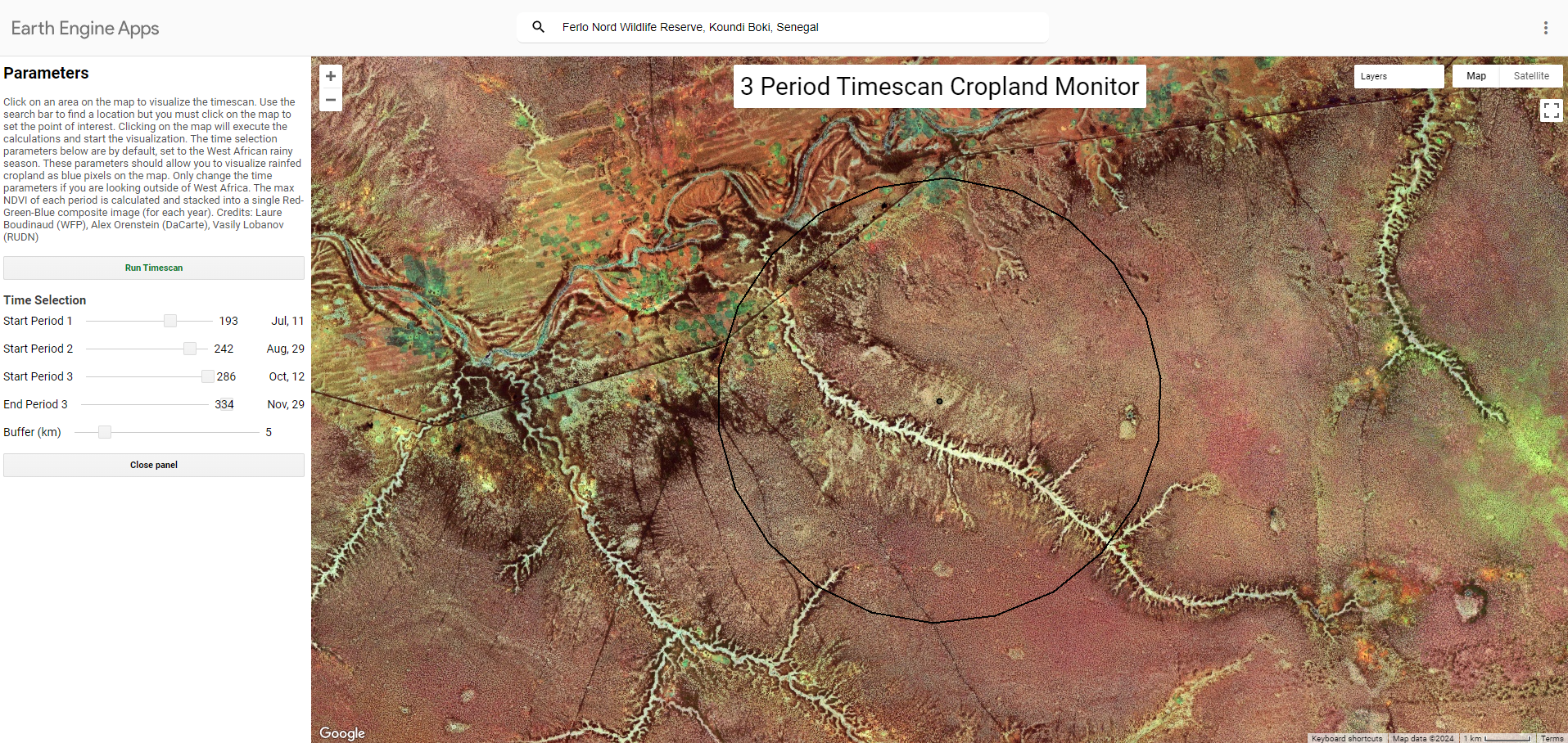

In 2014, Orenstein helped ACF develop an early-warning system, mining new knowledge sources utilizing distant sensing—observing the circumstances of grazing pastures from house through satellite tv for pc imagery and, in some circumstances, with using drones. He additionally labored with pastoralist organizations to assemble details about numerous circumstances on the bottom, starting from wildfire areas to the unfold of animal illness. He then started making maps utilizing open-access sources; passing the info by an algorithm that he developed to deal with and filter imagery, he created detailed and accessible illustrations of rainfall ranges and vegetation that grew to become a uncommon dependable useful resource for herders and their allies. Assist staff in warfare zones would print out his maps and cross them round to herders.

It was a part of a system designed to extract knowledge, analyze it, and ship it up the chain to establishments, together with nationwide ministries, UN companies, and donors. Having the ability to see crises coming, the considering went, would give institutional actors extra time and energy to organize their response and assign their assets. Having the ability to deploy emergency programming earlier would in flip afford herders a bit extra safety.

In apply, that’s not all the time the way it labored.

In the beginning of the wet season within the early summer time of 2017, Orenstein was monitoring rainfall patterns and felt a knot in his abdomen. The primary rains had hit too arduous, washing the dormant seeds out of the soil; a dry spell adopted that lasted for a number of weeks. When the rains did return, the grassland development was stunted. Drought was coming.

By mid-August, Orenstein was scribbling reviews and ringing journalists to warn that catastrophe was imminent. However when offered with this proof, the regional physique with the authority to declare an emergency didn’t act. By the point it lastly did, in April 2018—eight months after preliminary warnings had been sounded—it was far too late to reply successfully to what turned out to be the worst drought in 20 years.

Two months after that, in June 2018, the United Nations Workplace for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs urgently warned that 1.6 million kids confronted extreme acute malnutrition, up greater than 50% from the earlier yr.

That blighted season was additionally brutal for Sow. In March, his complete village despatched its animals south to flee the drought—the primary time anybody might bear in mind doing in order that early within the dry season. However Sow lingered, unwilling to take his sons out of faculty to assist him. Nonetheless, he additionally couldn’t afford to remain and purchase a number of tons of animal feed per 30 days at inflated costs. By the point Sow lastly employed just a few assistants and headed south along with his cattle, sands had engulfed the grasslands.

They marched throughout the desert like troopers at warfare, protecting 18 miles a day. On the 10th day, they reached the Tambacounda area by the Malian border, the place the cows would spend the remainder of the lean season grazing on savanna woodlands and luxurious forest. Not all of the herd survived the trek, and the cows that did had been emaciated and extra susceptible to insect-borne tropical ailments. By season’s finish, 1 / 4 of the herd had dropped useless—a defeat from which Sow nonetheless hasn’t recovered.

Democratizing knowledge

Driving by the Ferlo in 2018, Orenstein was distraught to see the rail-thin Fulani herders trailing behind their withering cows. Throughout the Sahel, anti-Fulani pogroms had been on the rise; some West Africans had been taking to Twitter to name for his or her extermination. As climate, meals, and safety programs broke down, it was simpler to scapegoat the drifting “foreigner” than to demand accountability from anybody accountable.

The mix of hunger and ethnic massacres reminded Orenstein of the tales his grandfather used to inform of surviving Auschwitz. What good had been early warnings if establishments weren’t prepared to behave on them? Not that the drought might have been prevented. However declaring an emergency sooner would have facilitated measures to melt its impression on herders. For instance, governments might have despatched money transfers and distributed meals for each people and livestock at strategic transit areas.

From that time on, Orenstein determined to do issues in another way. If establishments couldn’t be trusted to make good use of latest knowledge, why not get it on to herders?

However delivering knowledge to herders would show extraordinarily difficult. The centralized, vertically oriented programs historically used for knowledge assortment and evaluation are higher tailored to these establishments, normally positioned in capital cities, than to herders dispersed throughout 1000’s of miles of desert. What’s extra, Sahelian herders are a few of the world’s least reachable, least related folks. A lot of them don’t have cell telephones or entry to web or sturdy mobile service.

Nonetheless, the timing was good—support staff and donors had been more and more hopeful that expertise might clear up cussed issues. In 2018, Orenstein secured a $250,000 grant for ACF to broadcast knowledge reviews to herders in northern Senegal through textual content message and neighborhood radio.

The mission launched a number of months later, although by then Orenstein was already engaged on one other one: the Garbal name facilities. Much more than neighborhood radio, the decision facilities, that are a collaboration with the Netherlands Improvement Group, might supply knowledge tailor-made to people in very particular areas over a wider remit. The primary middle launched in Bamako, Mali, in 2018. One other, in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, adopted in 2019.

Orenstein and the Garbal group—roughly a dozen native knowledge analysts, mission managers, digital finance specialists, and tele-agents with levels in livestock administration and utilized agriculture—have designed totally different instruments for herders’ wants. For instance, they’ve provided methods to attach with veterinarians, evaluate market costs for animal feed, and use satellite tv for pc knowledge to search out seasonal migration corridors and monitor brushfires. Crucially, the group has additionally engaged straight with pastoralist organizations, coaching and equipping herders to ship again area knowledge about vegetation high quality in numerous zones—a bit of crucial data that’s undetectable through satellite tv for pc.

Orenstein himself went into the sphere as usually as he might to carry focus teams with herders and make sure that the way in which data was delivered could be tailored to their epistemic tradition. “As a substitute of asking them, ‘Do you want rainfall data?’ I’d say, ‘What sort of data do you want? And the way do you measure it?’” he remembers. “In any other case, the system would inform them to count on 25 millimeters of rain. Math is just not how they measure. So as an alternative, I’d maintain consultations on pond fullness, for instance, and outline rain power in these phrases—phrases they will use.”

Samba Ba, the Senegalese herder, notes how efficient this work has been in bridging the gulf between what tech had promised and what he and his friends really wanted. “Orenstein would assist us forecast in September what the vegetation could be like the next yr, so we might plan the following seasonal migration,” he says. “He got here to us within the area, took into consideration our customs, habits, and information, and used expertise to present us a clearer thought of the grazing state of affairs.”

Nonetheless, the most well-liked Garbal service has been its climate forecasting for rural zones. Beforehand, dependable data was severely missing, partially as a result of there weren’t sufficient floor stations and partially as a result of satellite tv for pc knowledge was accessible just for city areas. (Mali, as an illustration, has simply 13 lively climate stations, in contrast with 200 in Germany—a rustic one-third its measurement.)

Orenstein got here up with a option to make rural forecasts extra available. “We had the coordinates for each village in Burkina Faso. Why couldn’t we simply plug these into an API?” he remembers considering, referring to an utility programming interface, a form of middleman that permits functions to work together with each other. “All of the sudden, we had been getting climate forecasts for locations that weren’t listed anyplace.”

The API has enabled Garbal tele-agents to click on on distant pastoral zones on a map and obtain tables displaying weekly, day by day, and hourly forecasts which might be up to date with contemporary satellite tv for pc knowledge each three hours. Honoré Zidouemba, the mission supervisor for the Ouagadougou name middle, estimates that in the course of the wet season, his middle receives 2,000 to three,000 calls a day concerning the climate. “Herders and farmers used to derive data from pure cues,” he says, “however with local weather change, these are increasingly perturbed.”

It’s easy and cheap—costing below $100 a month to make use of—however of all of the group’s technological improvements, the API has made the most important impression. It’s a far cry from the sorts of higher-tech functions NGOs and growth organizations have been selling.

Since 2015, the World Financial institution has dedicated half a billion {dollars} to a two-phase mission to assist Sahelian herders’ “resilience” by methods that embrace growing technological instruments to map pastoral infrastructure. A senior humanitarian-agency staffer working with herders and expertise, who requested anonymity to talk frankly, says the ensuing databases haven’t been shared with herders; he calls the strategy, which is geared extra towards informing establishments than informing herders, “very technocratic.” (The World Financial institution didn’t reply to a request for remark.)

In the meantime, ACF, the French NGO Orenstein beforehand labored with, acquired worldwide consideration in 2020 for reportedly utilizing AI to assist herders, a declare a number of folks concerned within the mission say was merely incorrect. (“ACF doesn’t use self-learning for its Pastoral Early Warning System. Presently, the evaluation is finished ‘manually’ by human experience,” says Erwann Fillol, a knowledge evaluation skilled on the group.)

Different teams are experimenting with utilizing predictive analytics to forecast displacements and herders’ actions. A pilot mission from the Danish Refugee Council in Burkina Faso, for instance, predicts subnational displacement three to 4 months into the long run, permitting support staff to pre-position reduction. “Anticipatory motion in response to local weather hazards might be extra well timed, dignified, and value efficient than options,” says Alexander Kjaerum, an skilled on knowledge and predictive analytics with the group. “AI is a final choice when different issues fail. After which it does add worth.”

Nonetheless, some argue these sorts of tasks have missed the purpose. “How are excessive expertise and AI going to handle land entry points for pastoralists? It’s questionable if there are technological fixes to what are political, socioeconomic, and ecological pressures,” says Higazi, the pastoralist skilled.

Blama Jalloh, a herder from Burkina Faso who heads the influential regional pastoralist group Billital Maroobé, echoes this broad sentiment, arguing that big-budget, high-tech efforts primarily simply produce research, not innovation.

Taking issues into its personal fingers, in 2022 Billital Maroobé organized the primary hackathon designed by and for Sahelian herders. Jalloh says the hackathon aimed to slim the hole between herders and tech builders who lack familiarity with herding life. It granted as much as $8,000 to startups from Mauritania and Mali to trace animals and introduce digital ID playing cards for herders, which might assist them cross borders extra seamlessly.

An unsure future

With three name facilities now open, and Orenstein serving as a distant technical advisor from the US, the Garbal group is striving to remain targeted and make their work sustainable.

However, the destiny of the mission is much past its supporters’ management. The area’s slide into violence reveals no signal of stopping. In consequence, although extra of the herders that Garbal got down to assist have began carrying smartphones charged with battery packs, they’re more and more being pushed out of cell vary.

Between 2018 and 2022, Burkina Faso witnessed one of many world’s fastest-growing displacement crises, with the variety of internally displaced folks exploding from 50,000 to 1.Eight million—nearly 10% of the inhabitants. Fulanis particularly had been focused for killing by safety forces and government-backed vigilantes, and in some areas which might be house to vital Fulani herding communities, militants destroyed as many as half the mobile-phone antennas. One tele-agent says the herders who did handle to name in from warfare zones advised her how completely satisfied they had been to succeed in the middle. After I visited the Ouagadougou name middle final yr, a tele-agent named Dousso, a 24-year-old with a livestock diploma who speaks French, Gourmantche, Dioula, and Moré, advised me that “the entire coups,” in addition to incidents by which jihadists took over markets, had been additionally making it more and more tough to get sure varieties of knowledge.

This could make the service much more significant the place it’s nonetheless accessible, says Catherine Le Come, a Garbal cofounder, pointing to Mali, the place Garbal continues to be accessible in some components of the nation that are actually minimize off from the state.

But Garbal, similar to different efforts to get knowledge to herders, faces the all the time urgent subject of tips on how to fund this work constantly over time.

Nonprofit tasks like ACF’s neighborhood radio and SMS bulletin alerts are pegged to funding cycles that run out after just a few years. In March 2021, as an illustration, as Sow marched his cows 140 miles east towards the Senegal River, he relied on geospatial knowledge he obtained by neighborhood radio and textual content message from two totally different NGOs, informing him the place pastures had been plentiful. However simply three months later, each tasks ran out of cash and stopped supplying data.

The Garbal name facilities try to construct a extra sustainable mannequin. The plan is to section out NGO sponsorship by 2026 and function as a public-private partnership between the state and phone operators. Garbal costs callers a modest charge—the equal of 5 cents a minute—and has plans to roll out on-line marketplaces and monetary merchandise to generate income.

“Expertise in itself has a lot of potential,” says Le Come. “However it’s the non-public sector that should consider and spend money on innovation. And the dangers it faces innovating in a context as fragile because the Sahel have to be shared with a public sector that sees consumer impression.” (Cedric Bernard, a French agro-economist who has labored with ACF, firmly disagrees; he insists that the data needs to be free, and that attempting to be worthwhile “goes the mistaken means.”) Moreover, the for-profit mannequin implies that Garbal—which got down to assist weak herders—is already pivoting towards offering providers to farmers, who make extra dependable prospects as a result of they’re simpler to succeed in and higher related. Zidouemba, the Ouagadougou mission supervisor, says that its callers are actually overwhelmingly farmers; herders, he estimates, account for simply 20% of the calls to the Burkina Faso middle.

Because the tides of knowledge that attain them ebb and circulation, the herders themselves are conscious that the actual work wanted to maintain their lifestyle going is a longer-term political effort. As I ready to depart the Ferlo this fall, the panorama nonetheless resplendent from the wet season, Sow pulled me apart. He was a modest man, however there was one thing he needed me to know. That very night time, he mentioned shyly, his eldest son, Abdoulsalif, was leaving Dakar for Paris to start graduate research on the Sorbonne, the place he had obtained a scholarship—a fruit of the sacrifice that Sow made in the course of the yr of the horrible drought.

I reached Abdoulsalif over WhatsApp just a few weeks later, by which era he had realized that Sciences Po was extra prestigious than the Sorbonne and enrolled there as an alternative. He’s finding out public coverage and plans to hunt work on pastoralist coverage within the Sahel after commencement.

“Herding is a phenomenal lifestyle, an area the place I really feel very completely satisfied,” Abdoulsalif advised me. “It’s extraordinary to see, so distant, the animals of their huge areas. Way more stunning than to stay in a spot with 4 partitions. Even in Paris, I really feel nostalgic for this life, this house of herders.”

Hannah Rae Armstrong is a author and coverage adviser on the Sahel and North Africa. She lives in Dakar, Senegal.