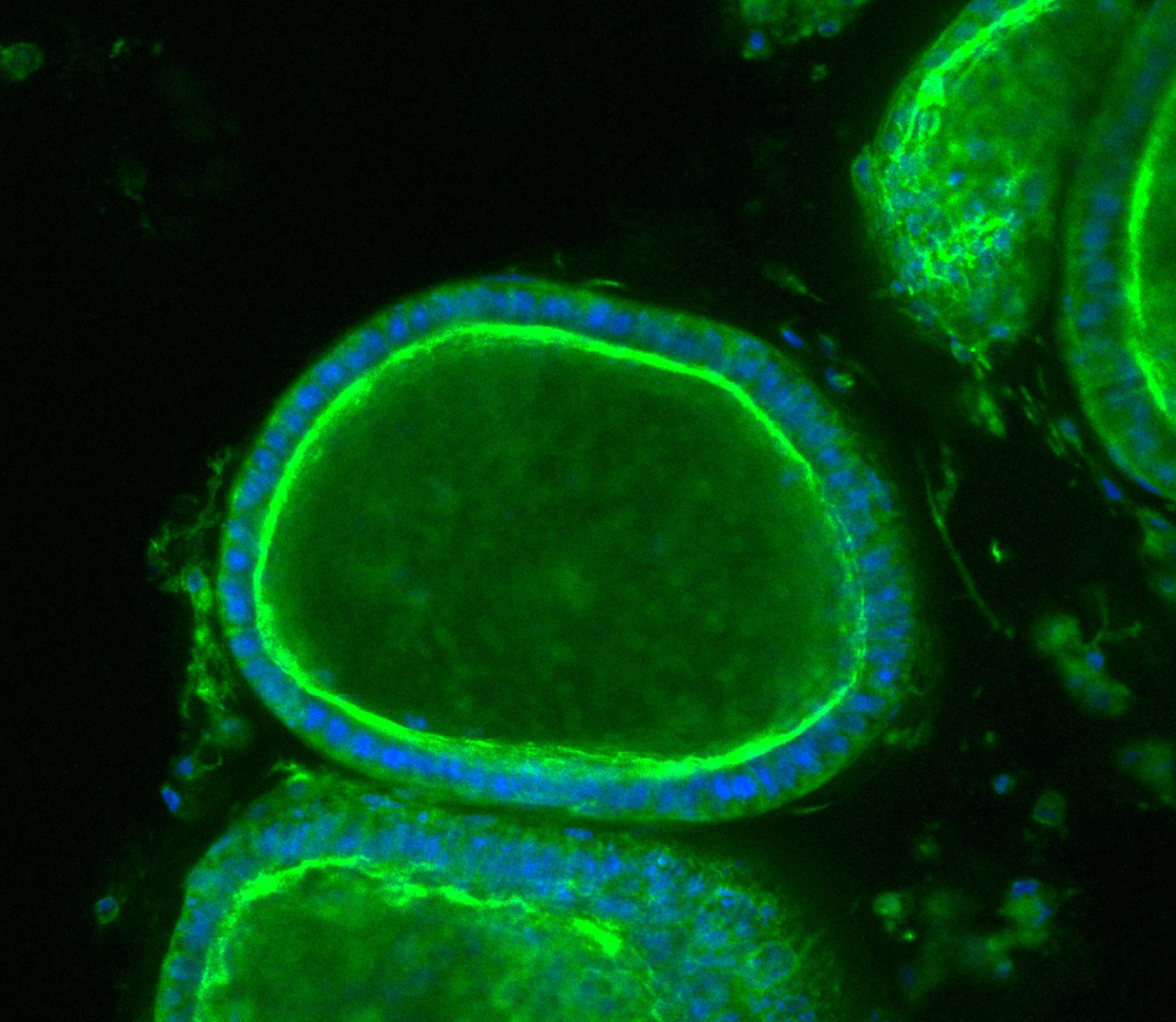

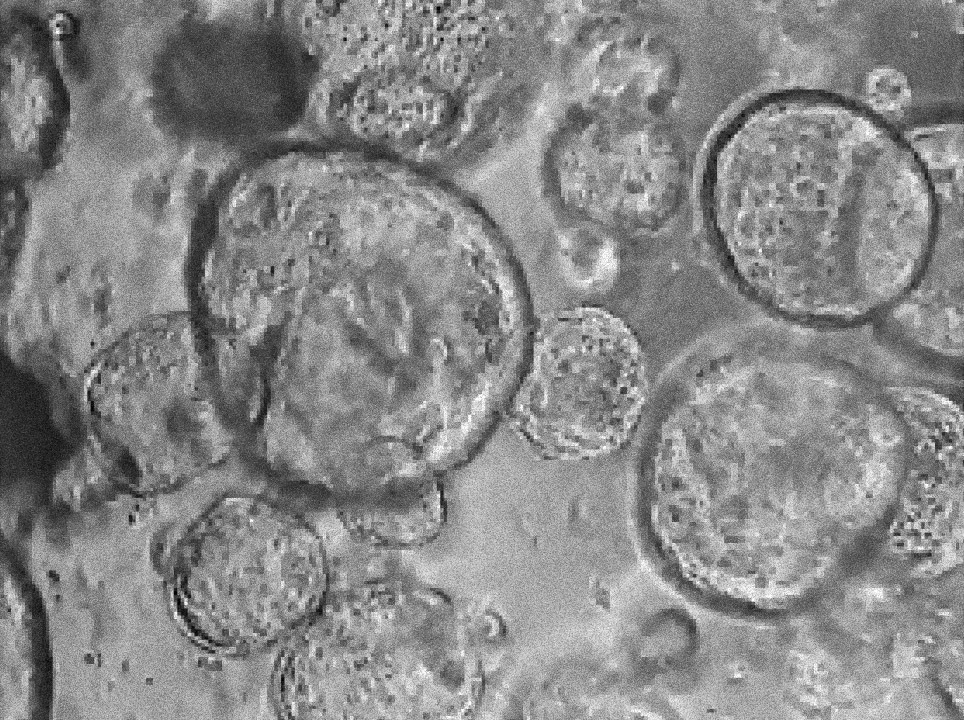

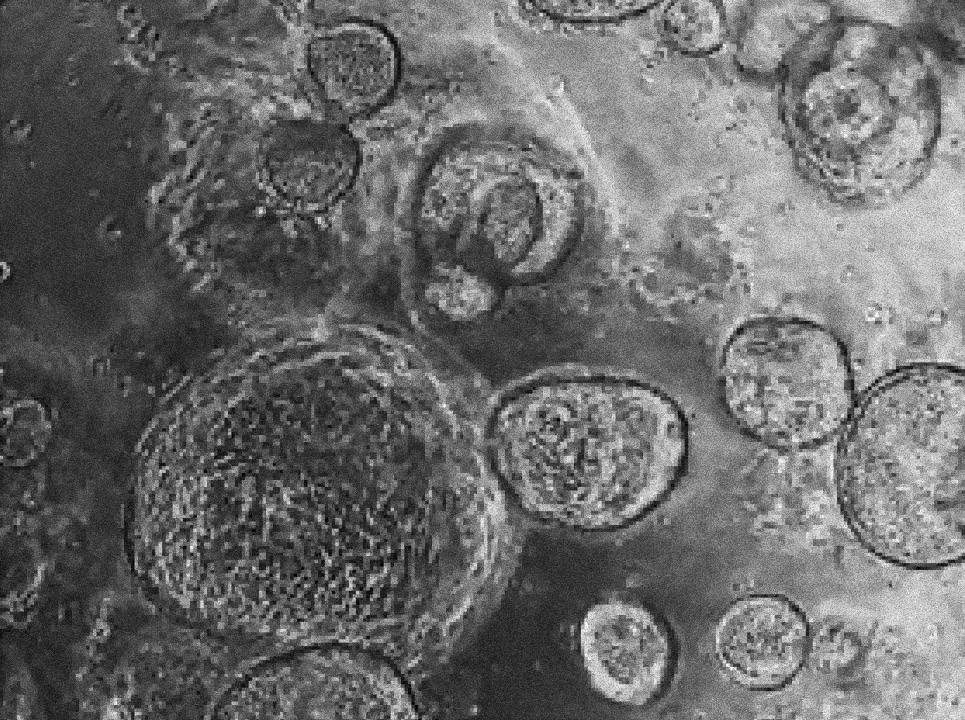

Within the heart of the laboratory dish, there was a delicate white movie that might solely be seen when the sunshine hit the proper approach. Ayse Nihan Kilinc, a reproductive biologist, popped the dish beneath the microscope, and a picture appeared on the connected display. As she centered the microscope, the movie resolved into clusters of droplet-like spheres with translucent interiors and skinny black boundaries. On this magnified view, the buildings ranged in dimension from as small as 1 / 4 to as giant as a golf ball. In actuality, every was solely as massive as a number of grains of sand.

“They’re rising,” Kilinc stated, observing that their plump shapes have been a promising signal. “These are good organoids.”

Kilinc, who works within the lab of organic engineer Linda Griffith at MIT, is amongst a small group of scientists utilizing new instruments akin to miniature organs to review a poorly understood—and ceaselessly problematic—a part of human physiology: menstruation. Heavy, typically debilitating intervals strike at the very least a 3rd of people that menstruate sooner or later of their lives, inflicting some to overlook weeks of labor or faculty yearly and jeopardizing their skilled standing. Anemia threatens about two-thirds of individuals with heavy intervals. And when menstrual blood flows by way of the fallopian tubes and into the physique cavity, it’s thought to typically create painful lesions—traits of a illness referred to as endometriosis, which may require a number of surgical procedures to manage.

Nobody is totally certain how—or why—the human physique choreographs this month-to-month dance of mobile delivery, maturation, and dying. Many individuals desperately want remedies to make their interval extra manageable, nevertheless it’s tough for scientists to design drugs with out understanding how menstruation actually works.

That understanding might be within the works, due to endometrial organoids—biomedical instruments constructed from bits of the tissue that traces the uterus, referred to as the endometrium. To make endometrial organoids, scientists acquire cells from a human volunteer and let these cells self-organize in laboratory dishes, the place they become miniature variations of the tissue they got here from. The analysis continues to be very a lot in its infancy. However organoids have already supplied insights into how endometrial cells talk and coordinate, and why menstruation is routine for some folks and fraught for others. Some researchers are hopeful that these early outcomes mark the daybreak of a brand new period. “I feel it’s going to revolutionize the best way we take into consideration reproductive well being,” says Juan Gnecco, a reproductive engineer at Tufts College.

An unusual downside

Durations are uncommon within the animal kingdom. The human physique goes by way of the menstrual cycle to arrange the uterus to welcome a fetus, whether or not one is prone to present up or not. In distinction, most animals put together the uterus solely as soon as a fetus is already current.

That cycle is a continuing sample of wounding and restore. The method begins when ranges of a hormone referred to as progesterone plummet, indicating that no child can be rising within the uterus that month. Eradicating progesterone triggers a response just like what occurs when the physique fights off an an infection. Irritation injures the endometrium. Over the following 5 or so days, the broken tissue sloughs off and flows out of the physique.

As quickly because the bleeding begins, the endometrium begins to heal. Over the course of about 10 days, this tissue quadruples in thickness. No different human tissue is understood to develop so extensively and so shortly—“not even aggressive most cancers cells,” says Jan Brosens, an obstetrician and gynecologist on the College of Warwick within the UK. Because the tissue heals—in a uncommon instance of scarless restore—it turns into an surroundings that may defend an embryo, which is a overseas entity within the physique, from an immune system educated to reject interlopers.

Scientists have crammed within the tough define of this course of after a long time of analysis, however many particulars stay opaque. How precisely the endometrium repairs itself so extensively is unknown. Why some folks have a lot heavier intervals than others stays an open query. And why people menstruate, moderately than reabsorbing unused endometrial tissue like many different mammals, is a matter of scorching debate amongst biologists.

This lack of expertise hampers scientists, who want to discover remedies for intervals which are too painful to be tamed by over-the-counter painkillers or too heavy to be absorbed by pads and tampons. Consequently, many individuals undergo. A research carried out within the Netherlands discovered that on common ladies misplaced a few week of productiveness per yr due to belly ache and different signs associated to their intervals. “It might not be uncommon for a affected person to see me within the clinic and say that each month, they needed to have two or three days off work,” says Hilary Critchley, a gynecologist and reproductive biologist on the College of Edinburgh.

Heavy intervals could make even every day duties tough. Getting up from a chair, for instance, might be an ordeal for somebody frightened about the potential for having stained the seat. Moms with low iron ranges are inclined to have infants with low delivery weights and different well being issues, so the consequences of heavy menstruation trickle down by way of generations. And but the uterus typically goes unacknowledged, even by researchers who’re exploring matters like tissue regeneration, to which the organ is clearly related, Brosens says. “It’s virtually unforgivable, in my opinion,” he provides.

Ask researchers why menstruation stays so enigmatic and also you’ll get quite a lot of solutions. Most everybody agrees there’s not sufficient funding to draw the variety of researchers the sector deserves—as is commonly the case for well being issues that primarily have an effect on ladies. The truth that menstruation is shrouded in taboos doesn’t assist. However some researchers say it has been laborious to seek out the proper instruments to review the phenomenon.

Scientists have a tendency to begin research of the human physique in different organisms, resembling mice, fruit flies, and yeast, earlier than translating the data again to people. These so-called “mannequin programs” reproduce shortly and might be altered genetically, and scientists can work with them with out working into as many moral or logistical issues as they’d in the event that they experimented on folks. However as a result of menstruation is so uncommon within the animal kingdom, it’s been robust to seek out methods to review the method exterior the human physique. “I feel that the principle limitations are mannequin programs, truthfully,” says Julie Kim, a reproductive biologist at Northwestern College.

Early adventures

Within the 1940s, the Dutch zoologist Cornelius Jan van der Horst was among the many first scientists to work on an animal mannequin for learning menstruation. Van der Horst was fascinated by uncommon, poorly studied critters, and this fascination led him to South Africa, the place he trapped and studied the elephant shrew. With an extended snout paying homage to an elephant’s trunk and a physique just like an opossum’s, the elephant shrew was already an oddball when van der Horst discovered that it’s one of many few animals that get a interval—a truth he in all probability found “kind of by chance,” says Anthony Carter, a developmental biologist on the College of Southern Denmark who wrote a overview of van der Horst’s work.

Elephant shrews will not be cooperative research topics, nevertheless. They solely menstruate at sure occasions of yr, they usually don’t do nicely in captivity. There’s additionally the problem of catching them, which van der Horst and his colleagues tried with hand-held nets. The shrews have been agile, so it was “typically a captivating however largely a disappointing sport,” he wrote.

Across the similar time, George W.D. Hamlett, a Harvard-based biologist, found another. Hamlett was inspecting preserved samples of a nectar-loving bat referred to as Glossophaga soricina when he observed proof of menstruation. The bats, which dwell primarily in Central and South America, weren’t simply accessible, so for a number of a long time his discovery remained merely a focal point within the scientific literature.

Then, within the 1960s, an keen graduate pupil named John J. Rasweiler IV enrolled at Cornell College. Rasweiler wished to review a kind of animal replica that mirrors what occurs in people, so his mentor identified Hamlett’s discovery. Maybe Rasweiler want to go discover some bats and see what he might do with them?

With an extended snout paying homage to an elephant’s trunk and a physique just like an opossum’s, the elephant shrew was already an oddball when van der Horst discovered that it’s one of many few animals that get a interval.

“It was a really difficult endeavor,” Rasweiler says. “Primarily I needed to invent every part from begin to end.” First there have been the journeys to Trinidad and Colombia to gather the bats. Then there was the difficulty of the best way to transport them again to america with out their getting crushed or overheating. (Delivery them in takeout meals containers, bundled collectively into a bigger package deal, turned out to work nicely.) As soon as the bats have been within the lab, he had to determine the best way to work with them with out letting them escape. He ended up setting up a walk-in cage on wheels that he might roll as much as the bats’ enclosures.

“I cherished working with them—pleasant animals,” says Rasweiler, who has since retired from a profession as a reproductive physiologist at SUNY Downstate. However different researchers have been postpone by the thought of working with a flying animal.

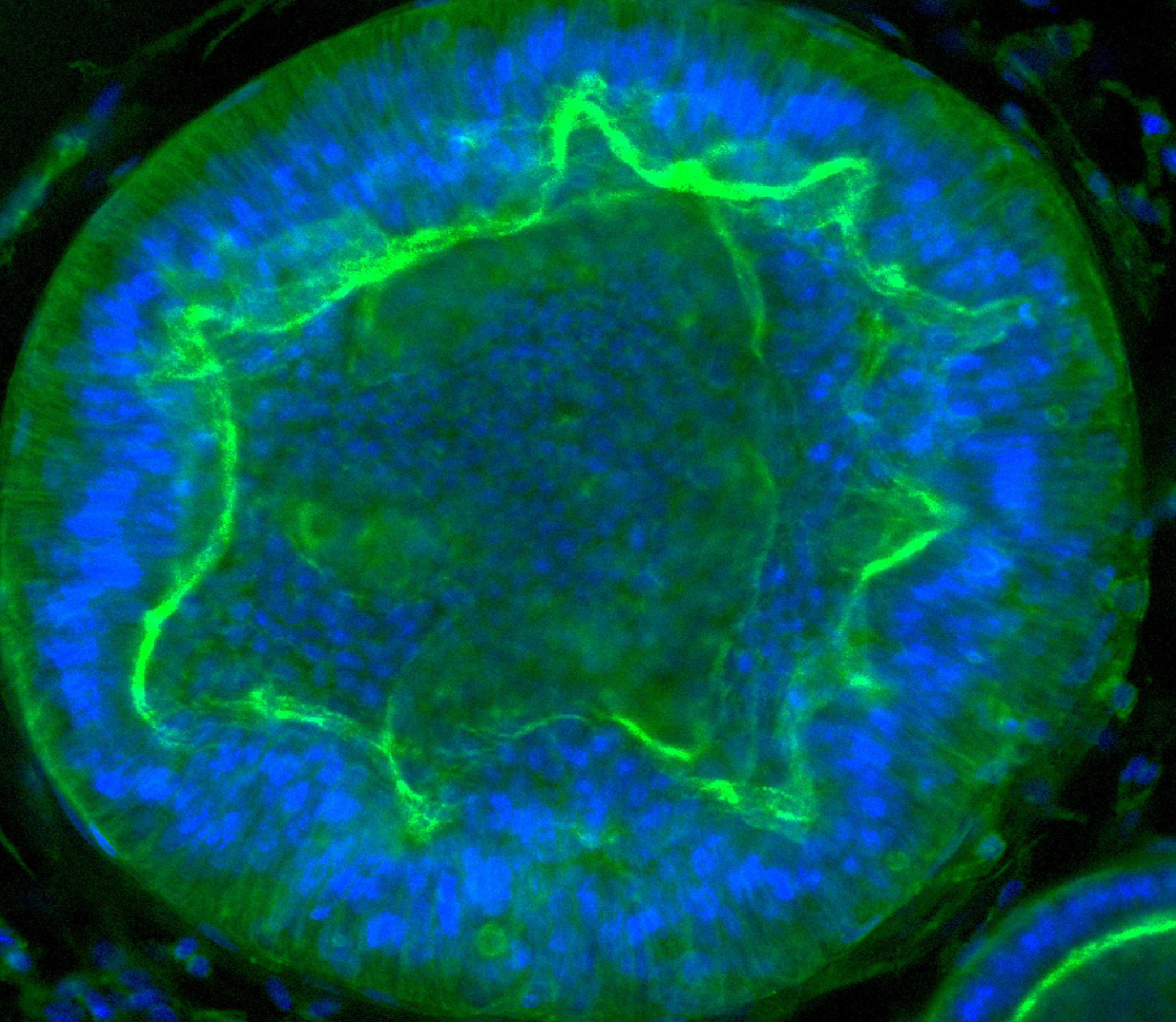

Researchers can observe how organoids reply to varied stimuli. Right here endometrial tissue thickens when uncovered to an artificial model of the hormone progesterone, mirroring the lead-up to menstruation. Picture supply: “Organoid co-culture mannequin of the biking human endometrium in a fully-defined artificial 2 extracellular matrix reveals epithelial-stromal crosstalk.” Juan S. Gnecco et al.

In 2016, the spiny mouse—a rodent that thrives within the dry situations of the Center East, South Asia, and components of Africa—joined the unique membership of animals recognized to menstruate. Spiny mice might be raised within the lab, so they could change into beneficial topics for menstruation analysis. However hundreds of thousands of years of evolution lie between people and mice, main Brosens to assume the genetics underlying their uteruses are prone to differ considerably.

A lot of the foundational work on menstruation has been carried out in macaque monkeys. However primates are costly to look after, and the Animal Welfare Act locations restrictions on primate analysis that don’t apply to different widespread lab animals. By means of a sequence of manipulations, scientists additionally discovered that they may power a standard lab mouse to have one thing just like a interval. This mannequin has been helpful, nevertheless it’s nonetheless solely a synthetic illustration of true human menstruation.

What researchers actually wanted was a approach to make use of people as research topics for menstruation analysis. However even setting apart the apparent moral issues, such a factor can be very difficult logistically. The endometrium evolves exceedingly shortly—“at an hourly fee, we see completely different responses from the cells, completely different capabilities,” says Aleksandra Tsolova, a cell biologist on the College of Calgary. “It’s very dynamic tissue.” Researchers would wish to carry out invasive biopsies virtually always to review it contained in the human physique, and even then, altering it genetically or by way of chemical remedies can be largely unattainable.

However by the early 1900s, an answer to this downside had already began to emerge. And it was not a creature from the jungle or the African grasslands that paved the street, however an organism from the underside of the ocean.

Organoids come on the scene

The groundwork for what would change into modern-day organoids was laid in 1910, when a zoologist named Henry Van Peters Wilson realized that cells from marine sponges have a kind of “reminiscence” of how they’re organized within the animal, even after they’re separated. When he dissociated a sponge by squeezing it by way of a mesh after which combined the cells collectively once more, the unique sponge re-formed. Midcentury work confirmed that sure cells from chick embryos have the same capacity.

In 2009, a research revealed within the journal Naturedescribed a doable approach of extending these observations to human organs. The researchers took a single grownup stem cell from a mouse gut—which had the power to change into any kind of intestinal cell—and embedded it in a gelatinous substance. The cell divided and, along with its progeny, shaped a miniature, simplified model of the intestinal lining. It was the primary time scientists had laid out a way of making an organoid from human tissue that was accessible to many labs and easy to adapt to different organs.

Since then, scientists have prolonged this normal strategy to imitate points of round a dozen human tissue varieties, together with these from the intestine, the kidneys, and the mind—and, by the late 2010s, the uterus.

It was a contented accident that introduced endometrial organoids into the combo. Within the years main as much as their improvement, scientists had been attempting to review the endometrium by rising its cells in easy layers on the bottoms of laboratory dishes. Stromal cells, which offer structural assist for the tissue and play a key position in being pregnant, proved straightforward to develop this fashion—these cells secrete a substance that sticks them to one another, and in addition makes them adhere to petri dishes. However epithelial cells, one other crucial element of the endometrium, posed an issue. In a dish, they stopped responding to hormones, and their shapes have been not like what’s seen within the human physique.

Then, whereas working with a mixture of human placental and endometrial tissue in an effort to get the placenta to kind organoids, a reproductive biologist named Margherita Turco observed one thing serendipitous. In the event that they have been suspended in a gel as an alternative of being grown in liquid, and given simply the correct mix of molecules from the human physique, endometrial epithelial cells assembled into tiny three-dimensional simulacra of the organ they got here from. “They grew actually, rather well,” Turco says. The truth is, endometrial organoids have been “type of overtaking the cultures.” One other group independently revealed related findings across the similar time.

At this time, placental and endometrial organoids are each beneficial instruments within the lab Turco runs on the Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Analysis in Basel, Switzerland. Her unique 2017 publication requires utilizing tissue from a biopsy, moderately than stem cells, to make organoids from the endometrium. Some labs as an alternative use tissue faraway from individuals who have had hysterectomies. However Turco’s lab lately confirmed that bits of the endometrium present in menstrual blood additionally work, which might imply the brand new endometrial organoids might be grown with out requiring biopsies or surgical procedure.

From all these beginning factors, researchers can now create microcosms of the human uterus. Every organoid reminds Tsolova of a tiny bubble suspended in a gelatinous dessert. And every presents a novel alternative to grasp processes that science has lengthy ignored.

Interval in a dish

Endometrial organoids grew to become integral to the work of the small neighborhood of researchers centered on the uterus. Since 2017, many labs have put their very own spins on these new instruments.

Kim’s lab has added stromal cells to the epithelial cells that make up traditional endometrial organoids. She and her colleagues combine the 2 collectively and easily let the mix “do its factor,” she says. The outcome is sort of a malt ball with stromal cells on the within and epithelial cells on the surface.

In 2021, Brosens and his colleagues created related buildings, which they name “assembloids.” As an alternative of blending the 2 cell varieties collectively, they created an organoid out of epithelial cells after which added a layer of stromal cells on high. Utilizing assembloids, they’ve discovered that deteriorating cells play a key position in serving to the embryo implant within the uterus. As a result of the endometrium is consistently dying and regrowing, the tissue is very versatile and capable of modify its form, Brosens explains. This helps the tissue kick-start being pregnant: “Maternal cells will seize the embryo,” he says, “and actually pull that embryo into the tissue.”

A video from certainly one of Brosens’s current publications exhibits an assembloid reworking round a five-day-old embryo. Earlier than he and his colleagues did this work, standard knowledge stated the endometrium was passive tissue that was invaded by the embryo, however that’s “simply utterly fallacious,” he says. This new understanding of how embryos implant might enhance in vitro fertilization and assist clarify why some persons are liable to miscarriages.

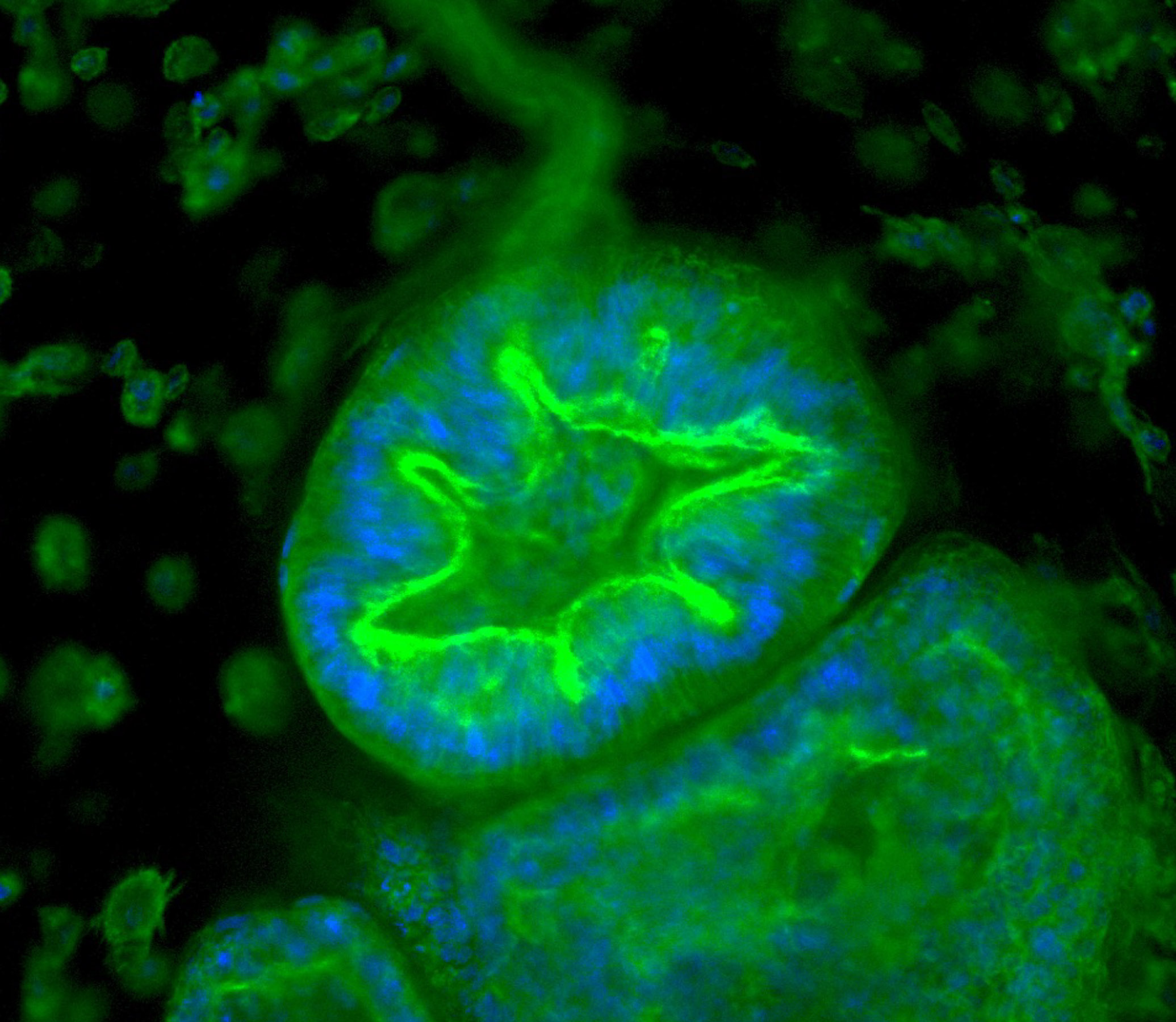

Margherita Turco’s laboratory on the Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Analysis in Switzerland has discovered that organoids derived straight from the endometrium (first picture) and from menstrual blood (second picture) of the identical individual have indistinguishable shapes and buildings. Picture supply: “Menstrual movement as a non-invasive supply of endometrial organoids.” Tereza Cindrova-Davies et al. communications biology.

Finally, Critchley hopes, scientists can design remedies that allow folks select when to have a interval—or in the event that they even wish to have one in any respect. Hormonal contraception can accomplish these targets for some, however these medicine may also trigger unscheduled bleeding that makes intervals tougher to handle, and a few folks discover the negative effects of the remedy insupportable.

To create higher choices, scientists nonetheless want to grasp how a standard interval works. Making an organoid menstruate in a dish can be an enormous boon for attaining this purpose, in order that’s what some researchers are attempting to do.

By manually including hormones to organoids, Gnecco and his collaborators can replicate a few of what the endometrium experiences over the course of a month. Because the cycle progresses, they see the cells adjusting the complement of genes they use, simply as they’d within the human physique. The form of the organoid additionally follows a well-recognized sample. Glands—infoldings of cells from which mucus and different substances are secreted—change from easy tubes to sawtooth-like buildings as this fake menstrual cycle progresses.

“It’s mind-blowing that we’re very, very near the affected person, however we’re not working throughout the affected person. There’s large potential.”

Aleksandra Tsolova, cell biologist, College of Calgary

With this technique working, the following step is to determine what occurs when the endometrium malfunctions. “That’s what actually received me excited,” Gnecco says. As a primary step, he handled organoids with an inflammatory molecule referred to as IL-1β, which is a trademark of the lesions that characterize endometriosis. IL-1β induced organoids to develop quickly, however solely when stromal cells have been combined in together with the epithelial cells. This means that alerts from stromal cells is likely to be a part of what causes endometriosis to develop right into a painful situation.

In the meantime, Kilinc is attempting to grasp why some folks’s intervals are so heavy. Endometrial tissue rising into the muscle that traces the uterus appears to trigger lesions, which might be one supply of extreme bleeding. To see how such lesions might kind, Kilinc watches how endometrial organoids react after they hit a dense gel, which mimics the feel of muscle.

In a delicate gel, endometrial organoids keep a pleasant, spherical construction. However when the organoid is in a stiff gel, it’s a unique story. A video from certainly one of Kilinc’s current experiments exhibits an organoid pulsating and squirming, virtually like a pot of water that’s about to boil over. Lastly, a gaggle of cells shoots off, creating an appendage-like construction that punctures the stiff gel. Movies like this make Kilinc assume that contact with muscle is likely to be among the many triggers that trigger the endometrium to begin wounding this tissue and inflicting heavy bleeding. “However,” she provides, “this isn’t clear but—we’re nonetheless investigating.”

Speedier science

At this time’s endometrial organoids can’t do every part animal fashions can do. For one factor, they don’t but embody key elements of menstruation, like blood vessels and immune cells. For one more, they’ll’t reveal how distant components of the physique, just like the mind, affect what occurs within the uterus. However as a result of they’re derived from human tissue, they’re intimately associated to the weird, idiosyncratic course of that could be a human interval, and that’s price rather a lot. “It’s mind-blowing that we’re very, very near the affected person, however we’re not working throughout the affected person,” Tsolova says. “There’s large potential.”

In parallel to the work on organoids, scientists have created an “organ on a chip” that mimics the endometrium. Tiny tubes affixed to a flat floor carry liquids to endometrial tissue, mimicking the movement of blood or hormones transmitted from different components of the physique. A really perfect mannequin system might mix endometrial cells of their pure association—as in an organoid—with flowing liquids, as on a chip.

Already, organoids have helped researchers resolve previous puzzles. Researchers in Vienna, for instance, used this know-how to determine which genes trigger some endometrial cells to develop cilia—hair-like buildings that beat in coordination to maneuver liquid, mucus, and embryos throughout the uterus. Different researchers have used organoids to find out how endometrial cells mature all through the menstrual cycle. In the meantime, Kim and her colleagues used organoids to review how the endometrium responds to irregular hormone ranges, which can be a think about endometrial most cancers.

Individuals who menstruate have waited a very long time for researchers to deal with such questions. Burdensome intervals are sometimes seen as only a “ladies’s downside”—a mindset Tsolova disagrees with as a result of it ignores the truth that folks scuffling with menstruation typically can’t contribute their full vary of skills to their communities. “It’s a societal downside,” she says. “It impacts each individual, in each approach.”

Saima Sidik is a contract science journalist primarily based in Somerville, Massachusetts.