That is an excerpt from The Chinese language Pc: A International Historical past of the Data Age by Thomas S. Mullaney, revealed on Might 28 by The MIT Press. It has been evenly edited.

ymiw2

klt4

pwyy1

wdy6

o1

dfb2

wdv2

fypw3

uet5

dm2

dlu1 …

A younger Chinese language man sat down at his QWERTY keyboard and rattled off an enigmatic string of letters and numbers.

Was it code? Baby’s play? Confusion? It was Chinese language.

The start of Chinese language, a minimum of. These forty-four keystrokes marked the primary steps in a course of generally known as “enter” or shuru: the act of getting Chinese language characters to look on a pc monitor or different digital system utilizing a QWERTY keyboard or trackpad.

Throughout all computational and digital media, Chinese language textual content entry depends on software program packages generally known as “Enter Technique Editors”—higher generally known as “IMEs” or just “enter strategies” (shurufa). IMEs are a type of “middleware,” so-named as a result of they function in between the {hardware} of the person’s system and the software program of its program or utility. Whether or not an individual is composing a Chinese language doc in Microsoft Phrase, looking out the online, sending textual content messages, or in any other case, an IME is at all times at work, intercepting the entire person’s keystrokes and attempting to determine which Chinese language characters the person desires to supply. Enter, merely put, is the way in which ymiw2klt4pwyy … turns into a string of Chinese language characters.

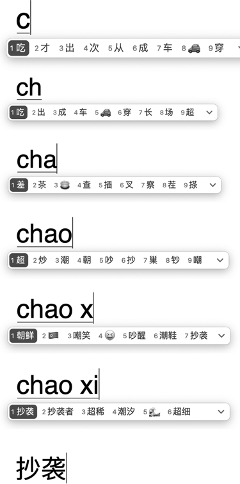

IMEs are stressed creatures. From the second a secret’s depressed, or a stroke swiped, they set off on a dynamic, iterative course of, snatching up user-inputted knowledge and looking out laptop reminiscence for potential Chinese language character matches. The most well-liked IMEs today are based mostly on Chinese language phonetics—that’s, they use the letters of the Latin alphabet to explain the sound of Chinese language characters, with mainland Chinese language operators utilizing the nation’s official Romanization system, Hanyu pinyin.

This younger man’s identify was Huang Zhenyu (additionally identified by his nom de guerre, Yu Shi). He was one in every of round sixty contestants that day, every carrying a shiny crimson shoulder sash—like a tickertape parade of previous, or a magnificence pageant. “Love Chinese language Characters” (Ai Hanzi) was emblazoned in vivid, golden yellow on a poster on the entrance of the corridor. The contestants’ process was to transcribe a speech by outgoing Chinese language president Hu Jintao, as rapidly and as precisely as they may. “Maintain Excessive the Nice Banner of Socialism with Chinese language Traits,” it started, or within the authentic: 高举中国特色社会主义伟大旗帜为夺取全面建设小康社会新胜利而奋斗. Huang’s QWERTY keyboard didn’t allow him to enter these characters immediately, nonetheless, and so he entered the quasi-gibberish string of letters and numbers as an alternative: ymiw2klt4pwyy1wdy6…

With these four-dozen keystrokes, Huang was properly on his means, not solely to successful the 2013 Nationwide Chinese language Characters Typing Competitors, but in addition to clock one of many quickest typing speeds ever recorded, wherever on the planet.

ymiw2klt4pwyy1wdy6 … isn’t the identical as 高举中国特色社会主义 … the keys that Huang truly depressed on his QWERTY keyboard—his “major transcript,” as we may name it—have been utterly completely different than the symbols that finally appeared on his laptop display, particularly the “secondary transcript” of Hu Jintao’s speech. That is true for each one of many world’s billion-plus Sinophone laptop customers. In Chinese language computing, what you kind isn’t what you get.

For readers accustomed to English-language phrase processing and computing, this could come as a shock. For instance, have been you to match the paragraph you’re studying proper now in opposition to a key log displaying precisely which buttons I depressed to supply it, the train can be unenlightening (to place it mildly). “F-o-r-_-r-e-a-d-e-r-s-_-a-c-c-u-s-t-o-m-e-d-_t-o-_-E-n-g-l-i-s-h … ” it might learn (forgiving any typos or edits). In English-language typewriting and laptop enter, a typist’s major and secondary transcripts are, in precept, an identical. The symbols on the keys and the symbols on the display are the identical.

Not so for Chinese language computing. When inputting Chinese language, the symbols an individual sees on their QWERTY keyboard are at all times completely different from the symbols that finally seem on the monitor or on paper. Each single laptop and new media person within the Sinophone world—irrespective of if they’re blazing-fast or molasses-slow—makes use of their system in precisely the identical means as Huang Zhenyu, always engaged on this iterative technique of criteria-candidacy-confirmation, utilizing one IME or one other. Not some Chinese language-speaking customers, thoughts you, however all. That is the primary and most elementary function of Chinese language computing: Chinese language human-computer interplay (HCI) requires customers to function solely in code on a regular basis.

If Huang Zhenyu’s mastery of a posh alphanumeric code weren’t spectacular sufficient, take into account the staggering velocity of his efficiency. He transcribed the primary 31 Chinese language characters of Hu Jintao’s speech in roughly 5 seconds, for an extrapolated velocity of 372 Chinese language characters per minute. By the shut of the grueling 20-minute contest, one extending over 1000’s of characters, he crossed the end line with an nearly unbelievable velocity of 221.9 characters per minute.

That’s 3.7 Chinese language characters each second.

Within the context of English, Huang’s opening 5 seconds would have been the equal of round 375 English words-per-minute, together with his total competitors velocity simply surpassing 200 WPM—a blistering tempo unmatched by anybody within the Anglophone world (utilizing QWERTY, a minimum of). In 1985, Barbara Blackburn achieved a Guinness E-book of World Information–verified efficiency of 170 English words-per-minute (on a typewriter, no much less). Pace demon Sean Wrona later bested Blackburn’s rating with a efficiency of 174 WPM (on a pc keyboard, it must be famous). As spectacular as these milestones are, the very fact stays: had Huang’s efficiency taken place within the Anglophone world, it might be his identify enshrined within the Guinness E-book of World Information as the brand new benchmark to beat.

Huang’s velocity carried particular historic significance as properly.

For an individual residing between the years 1850 and 1950—the interval examined within the guide The Chinese language Typewriter—the thought of manufacturing Chinese language by mechanical means at a price of over 200 characters per minute would have been nearly unimaginable. All through the historical past of Chinese language telegraphy, relationship again to the 1870s, operators maxed out at maybe a couple of dozen characters per minute. Within the heyday of mechanical Chinese language typewriting, from the 1920s to the 1970s, the quickest speeds on file have been simply shy of eighty characters per minute (with the vast majority of typists working at far slower charges). When it got here to trendy data applied sciences, that’s to say, Chinese language was persistently one of many slowest writing programs on the planet.

What modified? How did a script so lengthy disparaged as cumbersome and helplessly complicated all of the sudden rival—exceed, even—computational typing speeds clocked in different components of the world? Even when we settle for that Chinese language laptop customers are by some means capable of have interaction in “actual time” coding, shouldn’t Chinese language IMEs lead to a decrease total “ceiling” for Chinese language textual content processing as in comparison with English? Chinese language laptop customers have to leap via so many extra hoops, in any case, over the course of a cumbersome, multistep course of: the IME has to intercept a person’s keystrokes, search in reminiscence for a match, current potential candidates, and anticipate the person’s affirmation. In the meantime, English-language laptop customers want solely depress whichever key they want to see printed on display. What might be less complicated than the “immediacy” of “Q equals Q,” “W equals W,” and so forth?

To unravel this seeming paradox, we’ll study the primary Chinese language laptop ever designed: the Sinotype, also referred to as the Ideographic Composing Machine. Debuted in 1959 by MIT professor Samuel Hawks Caldwell and the Graphic Arts Analysis Basis, this machine featured a QWERTY keyboard, which the operator used to enter—not the phonetic values of Chinese language characters—however the brushstrokes out of which Chinese language characters are composed. The target of Sinotype was to not “construct up” Chinese language characters on the web page, although, the way in which a person builds up English phrases via the successive addition of letters. As a substitute, every stroke “spelling” served as an digital handle that Sinotype’s logical circuit used to retrieve a Chinese language character from reminiscence. In different phrases, the primary Chinese language laptop in historical past was premised on the identical type of “further steps” as seen in Huang Zhenyu’s prizewinning 2013 efficiency.

Throughout Caldwell’s analysis, he found sudden advantages of all these further steps—advantages solely remarkable within the context of Anglophone human-machine interplay at the moment. The Sinotype, he discovered, wanted far fewer keystrokes to discover a Chinese language character in reminiscence than to compose one via typical technique of inscription. By the use of analogy, to “spell” a nine-letter phrase like “crocodile” (c-r-o-c-o-d-i-l-e) took much more time than to retrieve that very same phrase from reminiscence (“c-r-o-c-o-d” can be sufficient for a pc to make an unambiguous match, in any case, given the absence of different phrases with related or an identical spellings). Caldwell known as his discovery “minimal spelling,” making it a core a part of the primary Chinese language laptop ever constructed.

As we speak, we all know this method by a distinct identify: “autocompletion,” a technique of human-computer interplay during which further layers of mediation lead to sooner textual enter than the “unmediated” act of typing. Many years earlier than its rediscovery within the Anglophone world, then, autocompletion was first invented within the area of Chinese language computing.