A while earlier than the primary dinosaurs, two supercontinents, Laurasia and Gondwana, collided, forcing molten rock out from the depths of the Earth. As eons handed, the liquid rock cooled and geological forces carved this rocky fault line into Pico Sacro, an odd conical peak that sits like a wizard’s hat close to the northwestern nook of Spain.

At this time, Pico Sacro is commemorated as a holy website and rumored, within the native mythology, to be a portal to hell. However this magic mountain has additionally change into valued in trendy instances for a really totally different cause: the quartz deposits that resulted from these geological processes are a number of the purest on the planet. At this time, it’s a wealthy supply of the silicon used to construct laptop chips. From this dusty floor, the mineral is plucked and remodeled into an inscrutable black void of pure inorganic know-how, one thing that an artwork director may have dreamed as much as stand in for aliens or the mirror picture of earthly nature.

Ed Conway, a columnist for the Instances of London, catches up with this rock’s “epic odyssey” in his new e-book, Materials World: The Six Uncooked Supplies That Form Fashionable Civilization.

In a warehouse just some miles from the height, he finds a blinding pile of fist-size quartz chunks able to be shoveled right into a smoking coal-fired furnace operating at 1,800 °C, the place they’re enveloped in a robust electrical discipline. The method shouldn’t be what he anticipated—extra Lord of the Rings than Bay Space startup—however he relishes each near-mystical step that follows as quartz is coaxed into liquid silicon, drawn into crystals, and shipped to the cleanest rooms on the planet.

Conway’s quest to know how chips are made confronts the truth that nobody particular person, “even these engaged on the provision chain itself,” can actually clarify all the course of. Conway quickly discovers that even an industrial furnace is usually a scene of sorcery and marvel, partly due to {the electrical} present that passes by means of the quartz and coal. “Even after greater than 100 years of manufacturing, there are nonetheless issues individuals don’t perceive about what’s taking place on this response,” he’s advised by Håvard Moe, an govt on the Norwegian firm Elkem, one in every of Europe’s greatest silicon producers.

Conway explains that the silicon “wafers” used to make the brains of our digital economic system are as much as 99.99999999% pure: “for each impure atom there are primarily 10 billion pure silicon atoms.” The silicon extracted from round Pico Sacro leaves Spain already nearly 99% pure. After that, it’s distilled in Germany after which despatched to a plant outdoors Portland, Oregon, the place it undergoes what is probably its most entrancing transformation. Within the Czochralski or “CZ” course of, a chamber is stuffed with argon gasoline and a rod is dipped repeatedly into molten refined silicon to develop an ideal crystal. It’s very like conjuring a stalactite at warp pace or “pulling sweet floss onto a stick,” in Conway’s phrases. From this we get “one of many purest crystalline constructions within the universe,” which may start to be formed into chips.

Materials World is one in every of a spate of latest books that purpose to reconnect readers with the bodily actuality that underpins the worldwide economic system. Conway’s mission is shared by Wasteland: The Secret World of Waste and the Pressing Seek for a Cleaner Future, by Oliver Franklin-Wallis, and Cobalt Purple: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives, by Siddharth Kara. Every one fills in darkish secrets and techniques concerning the locations, processes, and lived realities that make the economic system tick.

Conway goals to disprove “maybe essentially the most harmful of all of the myths” that information our lives in the present day: “the concept that we people are weaning ourselves off bodily supplies.” It’s simple to persuade ourselves that we now reside in a dematerialized “ethereal world,” he says, dominated by digital startups, synthetic intelligence, and monetary providers. But there may be little proof that we have now decoupled our economic system from its churning starvation for sources. “For each ton of fossil fuels,” he writes, “we exploit six tons of different supplies—principally sand and stone, but in addition metals, salts, and chemical substances. At the same time as we residents of the ethereal world pare again our consumption of fossil fuels, we have now redoubled our consumption of every thing else. However, someway, we have now deluded ourselves into believing exactly the other.”

Conway delivers wealthy life tales of the sources with out which our world could be unrecognizable, overlaying sand, salt, iron, copper, oil, and lithium. He buzzes with pleasure at each stage, with a correspondent’s reward for quick-fire storytelling, revealing the world’s materials provide chains in an avalanche of anecdote and trivia. The availability chain of silicon, he exhibits, is each otherworldly and extremely fragile, encompassing huge, nameless industrial giants in addition to terrifyingly slender bottlenecks. Practically all the world provide of specialised containers for the CZ dipping course of, for instance, is produced by two mines within the city of Spruce Pine, North Carolina. “What if one thing occurred to these mines? What if, say, the only street that winds down from them to the remainder of the world was destroyed in a landslide?” asks Conway. “Quick reply: it will not be fairly. ‘Right here’s one thing scary,’ says one veteran of the sector. ‘In case you flew over the 2 mines in Spruce Pine with a crop duster loaded with a really explicit powder, you may finish the world’s manufacturing of semiconductors and photo voltaic panels inside six months.’” (Conway declines to print the title of the substance.)

But after such a powerful journey by means of deep time and the world economic system, how lengthy will any digital gadget final? The helpful lifetime of our electronics and plenty of different merchandise is prone to be a brief blip earlier than they return to the earth. As Oliver Franklin-Wallis writes in Wasteland, digital waste is one cussed a part of the two billion tons of stable waste we produce globally annually, with the common American discarding greater than 4 kilos of trash every day.

Wasteland begins with a visit to Ghazipur, India, the “largest of three mega-landfills that ring Delhi.” There, amid an fragrant fug of sticky-sweet vapors, Franklin-Wallis stomps by means of a swamp-like morass of trash, following his information, an area waste picker named Anwar, who helps him acknowledge stable stepping-stones of trash in order that he might safely navigate above the perilous system of subterranean rivers that rush someplace unseen under his ft. Just like the hidden icy currents that carve by means of glaciers, these rivers make the trash mountain susceptible to cleaving and crumbling, resulting in round 100 deaths a 12 months. “Over time, [Anwar] explains, you study to learn the waste the best way sailors can learn a river’s present; he can intuit what’s prone to be stable, what isn’t. However collapses are unpredictable,” Franklin-Wallis writes. For all its aura of decay, that is additionally a residing panorama: there are tomato vegetation that develop from the refuse. Waste pickers eat the fruits off the vine.

Wasteland is finest when excavating the tales buried within the dump. In 1973, lecturers on the College of Arizona, led by the archaeologist William Rathje, turned the examine of landfills right into a science, labeling themselves the “garbologists.” “Trash, Rathje discovered, may inform you extra a few neighborhood—what individuals eat, what their favourite manufacturers are—than cutting-edge client analysis, and predict the inhabitants extra precisely than a census,” Franklin-Wallis writes. “Not like individuals,” he provides, “rubbish doesn’t lie.”

Wasteland leaves an enduring impression of the trash-worlds that we make. Most horrifying of all, the contents of landfills don’t decompose the best way we anticipate. By taking geological cores from landfills, Rathje discovered that even a long time later, our waste stays a morbid museum: “onion parings have been onion parings, carrot tops have been carrot tops. Grass clippings which may have been thrown away the day earlier than yesterday spilled from cumbersome black garden and leaf baggage, nonetheless tied with twisted wire.”

Merely shifting to “sustainable” or “cleaner” applied sciences doesn’t remove the economic fallout from our consumption.

Franklin-Wallis’s histories assist inform us the place we as a civilization started to go fallacious. In historical Rome, waste from public latrines was washed away with wastewater from the town’s fountains and bathhouses, requiring a “complicated underground sewer system topped by the Cloaca Maxima, a sewer so nice that it had its personal goddess, Cloacina.” However by the Victorian age, the principally round economic system of waste was coming to an finish. The grim however eco-friendly job of turning human effluent into farm fertilizer (so-called “nightsoil”) was made out of date by the adoption of the house flushing bathroom, which pumped effluent out into rivers, typically killing them. Karl Marx recognized this as the start of a “metabolic rift” that—later turbocharged by the event of disposable plastics—turned a sustainable cycle of waste reuse right into a conveyor between metropolis and dump.

This meditation on trash may be fascinating, however the e-book by no means fairly lands on an enormous concept to attract its story ahead. Whereas trash piles may be locations of discovery, our propensity to make waste isn’t any revelation; it’s an ever-present nightmare. Many readers will arrive in the hunt for solutions that Wasteland isn’t providing. Its suggestions are in the end modest: the writer resolves to purchase much less, learns to stitch, appreciates the Japanese artwork of kintsugi (mending pottery with valuable metals to spotlight the act of restore). A handful of different life-style selections comply with.

As Franklin-Wallis is fast to acknowledge, a journey by means of our personal waste can really feel hopeless and overwhelming. What we’re missing are viable methods to steer our societies from the extremely resource-intensive paths they’re on. This thought, taken up by designers and activists driving the Inexperienced New Deal, is aiming to show our consideration away from dwelling on our private “footprint”—a murky concept that Franklin-Wallis traces to business teams lobbying to deflect blame from themselves.

Reframing each waste and provide chains as issues which are political and worldwide, slightly than private, may information us away from guilt and transfer us towards options. As an alternative of manufacturing and waste as separate issues, we are able to consider them as two points of 1 nice problem: How can we construct properties, design transport techniques, develop know-how, and feed the world’s billions with out creating manufacturing unit waste upstream or trash downstream?

Republic of Congo.

Merely shifting to “sustainable” or “cleaner” applied sciences doesn’t remove the economic fallout from our consumption, as Siddharth Kara reveals in Cobalt Purple. Cobalt is part of nearly each rechargeable gadget—it’s used to make the positively charged finish of lithium batteries, for instance, and every electrical automobile requires 10 kilograms (22 kilos) of cobalt, 1,000 instances the amount in a smartphone.

Half the world’s reserves of the aspect are present in Katanga, within the south of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which places this resource-rich area on the heart of the worldwide vitality transition. In Kara’s telling, the cobalt rush is one other chapter in an age-old story of exploitation. Within the final two centuries, the DRC has been a middle not just for the bloody commerce in enslaved people but in addition for the colonial extraction of rubber, copper, nickel, diamonds, palm oil, and rather more. Barely a contemporary disaster has unfolded with out sources stolen from this soil: copper from the DRC made the bullets for 2 world wars; uranium made the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki; huge portions of tin, zinc, silver, and nickel fueled Western industrialization and world environmental crises. In return, the DRC’s 100 million individuals have been left with little by means of lasting advantages. The nation nonetheless languishes on the foot of the United Nations improvement index and now faces disproportionate impacts from local weather change.

In Cobalt Purple, Congo’s historical past performs out in vignettes of barbarous theft perpetrated by highly effective Western-backed elites. Kara, an writer and activist on trendy slavery, constructions the e-book as a journey, drawing frequent parallels to Joseph Conrad’s 1899 Coronary heart of Darkness, with the town of Kolwezi substituting for Kurtz’s ivory-trading station, the vacation spot within the novella. Kolwezi is the middle of Katanga’s cobalt commerce. It’s “the brand new coronary heart of darkness, a tormented inheritor to these Congolese atrocities that got here earlier than—colonization, wars, and generations of slavery,” Kara writes. The e-book supplies a speedy abstract of the nation’s historical past beginning with the colonial vampirism of the Belgian king Leopold’s “Free State,” described by Conrad because the “vilest scramble for loot that ever disfigured the historical past of human conscience.” The king’s personal colony pressured its topics to gather rubber beneath a system of quotas enforced by systematic execution and disfigurement; pressured labor continued nicely into the 20th century in palm oil plantations that provided the multinational Unilever firm.

These three books supply to attach the reader to the texture and scent and rasping actuality of a world the place supplies nonetheless matter.

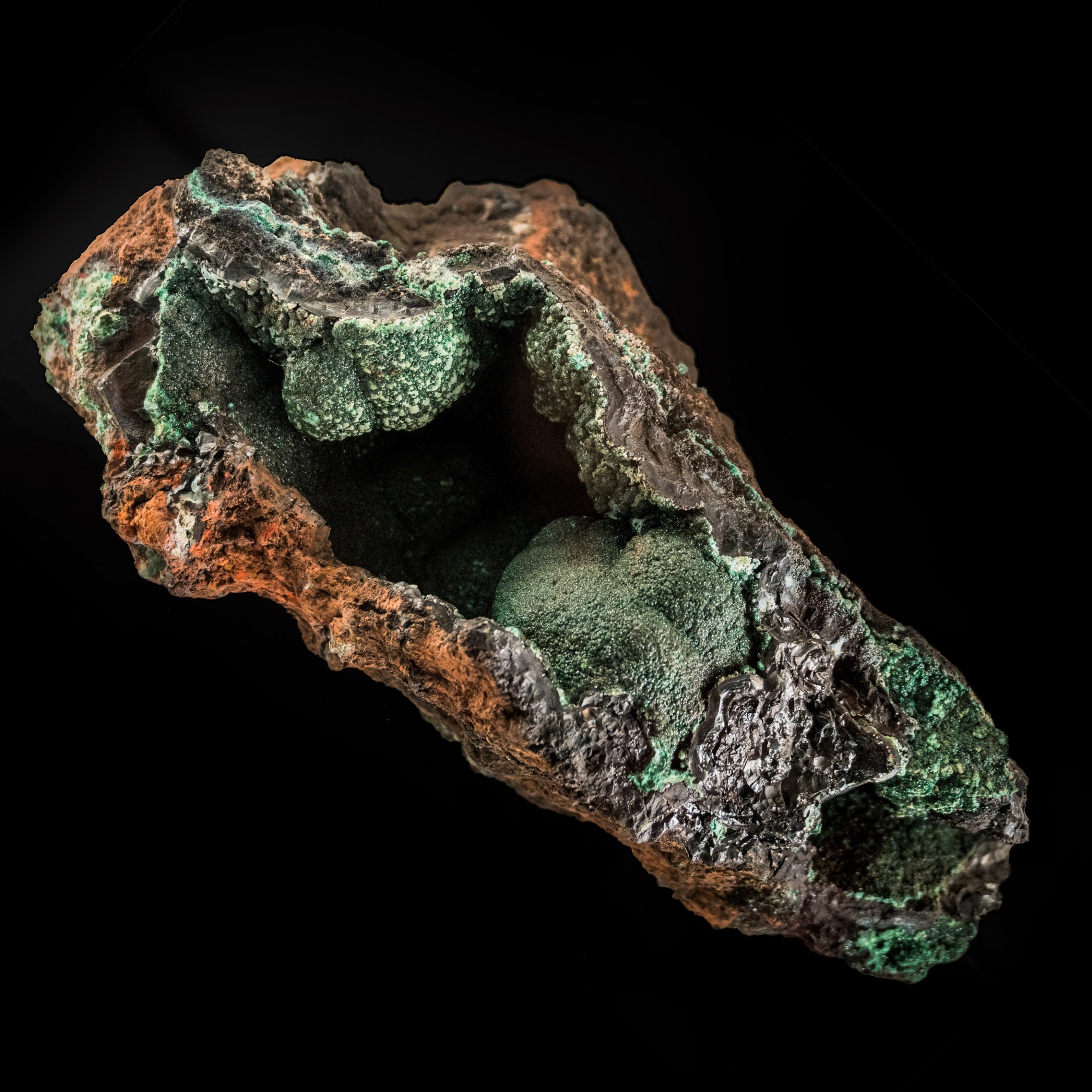

Kara’s multiyear investigation finds the patterns of the previous repeating themselves in in the present day’s inexperienced growth. “As of 2022, there isn’t a such factor as a clear provide chain of cobalt from the Congo,” he writes. “All cobalt sourced from the DRC is tainted by varied levels of abuse, together with slavery, baby labor, pressured labor, debt bondage, human trafficking, hazardous and poisonous working circumstances, pathetic wages, harm and demise, and incalculable environmental hurt.” Step-by-step, Kara’s narrative strikes from the fringes of Katanga’s mining area towards Kolwezi, documenting the free movement of minerals between two parallel techniques supposedly divided by a firewall: the formal industrial system, beneath the auspices of mining giants which are signatories to sustainability pacts and human rights conventions, and the “artisanal” one, by which miners with no formal employer toil with shovels and sieves to provide a number of sacks of cobalt ore a day.

We study of the system of creuseurs and négociants—diggers and merchants—who transfer the ore from denuded fields into the formal provide chain, revealing that an unknown share of cobalt offered as moral comes from unregulated toil. If Materials World tells a neat story of capitalism’s invisible hand, the drive that whisks sources across the planet, Cobalt Purple paperwork a extra brutal and opaque mannequin of extraction. In Kara’s telling, the artisanal system is grueling and inefficient, involving numerous middlemen between diggers and refineries who serve no objective besides to launder ore too low-grade for industrial miners and obscure its origins (whereas skimming off a lot of the earnings).

In every single place Kara finds artisanal mining, he finds kids, together with women, some with infants on backs, who huddle collectively to protect in opposition to the specter of sexual assault. There isn’t any scarcity of haunting tales from the frontlines. Cobalt ore binds with nickel, lead, arsenic, and uranium, and publicity to this steel combination raises the chance of breast, kidney, and lung cancers. Lead poisoning results in neurological harm, decreased fertility, and seizures. In every single place he sees rashes on the pores and skin and respiratory illnesses together with “laborious steel lung illness,” brought on by continual and doubtlessly deadly inhalation of cobalt mud.

One girl, who works crushing 12-hour days simply to fill one sack that she will commerce for the equal of about 80 cents, tells how her husband just lately died from respiratory sickness, and the 2 instances she had conceived each resulted in miscarriage. “I thank God for taking my infants,” she says. “Right here it’s higher to not be born.” The e-book’s handful of genuinely devastating moments arrive like this—from the insights of Congolese miners, who’re too not often given the possibility to talk.

All of which leaves you to query Kara’s unusual determination to mould the narrative across the 125-year-old Coronary heart of Darkness. It has been half a century for the reason that Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe condemned Conrad’s novella as a “deplorable e-book” that dehumanized its topics even because it aimed to encourage sympathy for them. But Kara doubles down by mirroring Conrad’s storytelling gadget and elegance, from the primary sentence (that includes “wild and wide-eyed” troopers wielding weapons). When Kara describes how the “filth-caked kids of the Katanga area scrounge on the earth for cobalt,” who’s the article of disgust: the forces of exploitation or the miners and their households, typically decreased to summary figures of struggling?

Following Conrad, Cobalt Purple turns into, primarily, a narrative of morality—an “unholy story” concerning the “malevolent drive” of capital—and reaches a equally moralistic conclusion: that we should all start to deal with artisanal miners “with equal humanity as every other worker.” If this looks like an ethereal response after the laborious work of detailing the intricacies of cobalt’s damaged provide chain, it’s doubly so after Kara paperwork each the previous waves of injustice and the ethical crusades which have introduced the Free State and outdated colonial constructions to an finish. Such requires humanistic equity towards Congo have echoed down the ages.

Form Fashionable Civilization

Ed Conway

Siddharth Kara

Oliver Franklin-Wallis

All three books supply to attach the reader to the texture and scent and rasping actuality of a world the place supplies nonetheless matter. However in Kara’s case, such a powerful concentrate on documenting firsthand expertise edges out a deeper understanding. There may be little area given to the quite a few students from throughout the African continent who’ve made sense of how politics, commerce, and armed teams collectively rule the DRC’s lethal mines. The Cameroonian historian Achille Mbembe has described websites like Katanga not solely as locations the place Western-style rule of regulation is absent however as “death-worlds” constructed and maintained by wealthy actors to extract sources at low value. Greater than merely making sense of the present disaster, these thinkers tackle the massive questions that Kara asks however struggles to reply: Why do the sources and actors change however exploitation stays? How does this sample finish?

Matthew Ponsford is a contract reporter based mostly in London.